SOUTH ASIA’S STRATEGIC SECURITY

ENVIRONMENT

Ehsan Mehmood Khan

Abstract

South Asia is home to nearly

one-fourth of humanity. It also has one of the largest arrays of territorial and

non-territorial disputes in the world. The region has witnessed several

interstate wars and warlike situations besides a number of intrastate

insurgencies, ethnic discords and confrontations in the last about seven

decades. As a consequence, the strategic security environment of the region is

overshadowed by traditional military security of the state. Human security of virtually 1.57

billion people remains hostage to the security perceptions based on the

nature of conflicts rather than human sufferings based on shared realities.

This paper analyzes key expressions and manifestations of the security paradigm

so as to recommend practicable measures for a comprehensive, cooperative and

holistic security framework.

Introduction

History,

geography, demography, and political opportunity structure intermix to

formulate national purpose, interests and inspirations of a state. National interests stipulate

economic, social and political priorities. These, in turn, shape a strategic

construct – strategic mindset and security paradigm – consistent with the power

potential of the nation. The string goes down to the lowest rung in a

manner that it receives light from the national purpose to the extent it must.

While economic, social and political concerns are debated openly by the

policymakers and strategic planners, they often downplay the imprints of

religion on decision making and policy formulation process. At any rate,

religious beliefs play a consequential role in evolution of strategic culture

and concerns of a country or region.

All

this is as much true in case of South Asian countries as it is for any other

state, whether big or small, developed or developing, and overtly theological

or ostensibly secular. However, South Asia’s strategic culture is quite

different from other major regions of the world because of its peculiar security

issues and atypical security calculus. Geo-historic, geo-political, geo-strategic and

geo-economic and geo-cultural dimensions together play their part in making and

maintaining the security construct of the region. Besides, security

interests of major powers of the world create an unbreakable interface thereby

leaving irremovable imprints on the regional security landscape.

South

Asia is one of the most

militarized zones in the world and home to inter-state and intra-state wars.

Having remained in a state of conflict for centuries, and especially since

1947, it has turned into a

“Corridor of Instability” on the globe. Security problems of the region range from traditional to

non-traditional and state security to human security. State security

overshadows human security in a number of ways, and people remain to be the

ultimate sufferers. Thus, the region is hostage to a security web of its own,

and would seemingly remain so in the decades to come.

Location and Makeup

Located

in the heart of Asia, the South Asian region physically stretches from the Hindu Kush to the Malay

Peninsula and from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas,[1]

and is bordered by the Middle East, Central Asia, China and South East Asia.

This way, it is a meeting

point for various important regions on the globe. Thus, events and activities in South

Asia directly affect the contiguous regions and indirectly affect

remaining parts of the world. Likewise, any sort of developments in the

adjacent regions, too, reflect on the South Asian affairs.

Traditionally,

South Asia has been

understood as a region comprising seven countries namely Pakistan, India,

Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and Maldives. However, an extended

definition of the area in keeping with the archives of the UN shows Afghanistan too as part of South

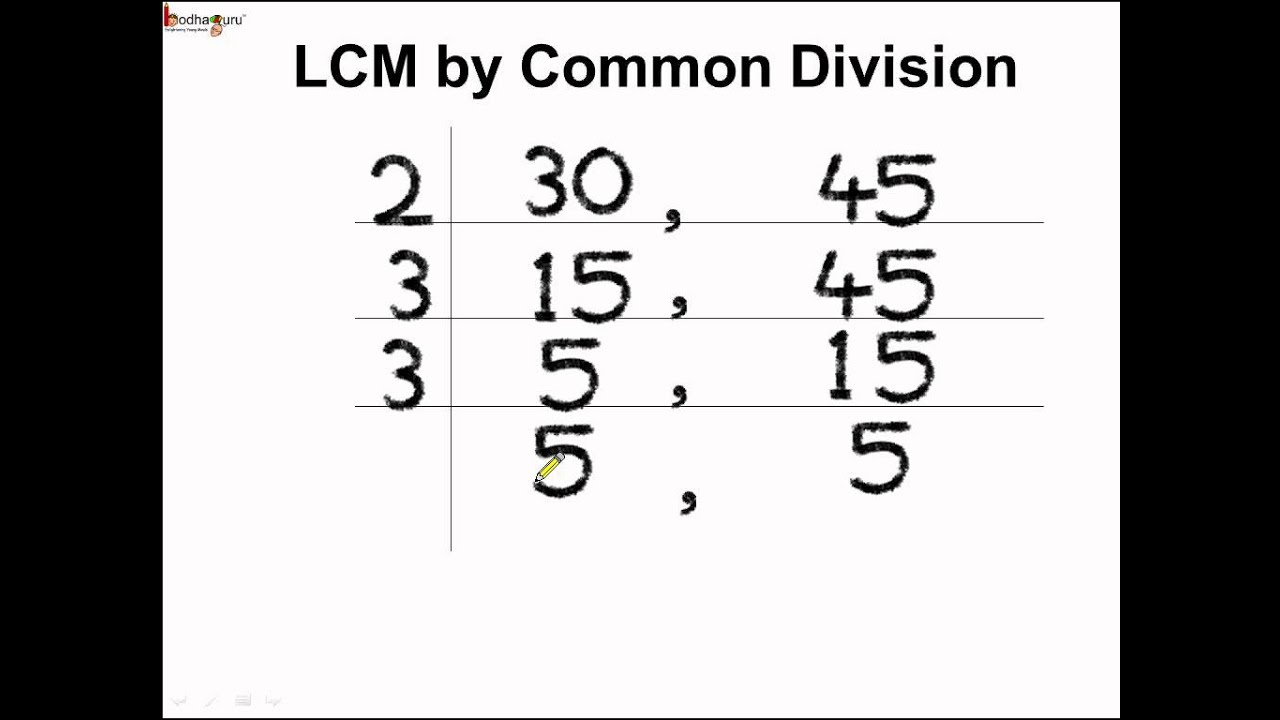

Asia. Figure-1 illustrates.[2]

It is of note that the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) initially consisted of

seven countries. Later, Afghanistan, too, became a member. The

composition of South Asia in this paper is, hence, based on the UN definition

of South Asia as well as present membership of SAARC.

There is a

unique mismatch between the population and landmass of the region (Figure-2).[3]

For instance, South Asia’s

population (1,577,744,692) when combined with that of China (1,338,612,968)

comes to 2,677,225,936 and is thus 54% of this total (Figure-3).[4]

On the other hand, the region

has nearly 35% of the territorial area when combined with that of China

(9,596,961 square kilometre). Similarly, compared with the European Union, the region has

virtually thrice more population (1,577,744,692 vis-à-vis 491,582,852).

To put it in global comparison, South Asia has 23.23% of world population (6,790,062,216) dwelling

on 1% of the globe (510.072 million square kilometre).[5]

These comparisons have been given herein for the reason that demographic and

territorial composition of South Asia has a concrete linkage with makeup of its

security paradigm.

South Asia has a diverse territory ranging from fertile plains to

vast desert stretches and the highest mountain ranges in the world. To

note, top thirteen

mountain peaks of the world are located in the Karakoram and Himalaya mountain

ranges of South Asia.[6]

The region has tremendous tapped and untapped natural resources. Throughout the

recorded history of the region, it attracted traders and invaders especially

from the Central Asia and the Middle East. Intermarriages, immigration and

settlements changed the demography of the region to a great extent. Likewise,

it paved a way for new religions and languages. Today, South Asia is home to a number of major world

religions, ethnic tribes, races and languages. All these are inalienable

features of security outlook in the region. There are numerous other

expressions e.g. sects within Islam and Christianity, and castes within

Hinduism. Thus, South Asia has tremendous heterogeneity, which adds complexity

to the already intricate security atmosphere.

Inter-state conflicts involve huge unsettled

territory; indeed, unparalleled with territorial disputes elsewhere in

the world. This, source of conflict, is the most dangerous dimension of

security in the region. This needs dexterity and statesmanship on part of the

South Asian leadership so as to manage security and maintain stability in the

region. With unsettled

inter-state disputes and unmediated intra-state ethnic interests, human

security atmosphere of the region remains clothed in despair and desolation.

This calls for a regional

approach to interconnection, interdependence, integration and unity within the

diversity, which is supported by the UN Charter, too.[7]

Dynamics and Manifestations of

Security Paradigm

South

Asia is at war with itself. This densely populated chunk of territory on the

globe is heavily

militarized too. The region

is carrying the burden of history. Historical memories of the partition of India in 1947,

the colonial legacies

and more so, the Muslim

rule in India before the British colonized it, have left strong imprints

on the hearts and minds of the people, which are acting as psychological

determinant in virtually all human affairs including the statecraft. It is here

that the religion interacts with security. These are, thus, a major impediment

on the way to concord and conciliation, and a stumbling block for regional

security and stability. The state

policies are influenced by political concerns and security perceptions from top

to bottom. Due to the same reasons, even the most technical issues pending solution, often,

transform into geo-political moorings and politico-military disputes.

This has given birth to an intricate security template and conflict landscape.

South

Asia’s dynamics of conflict that shape up the regional security environment have four principal

motivations namely the historical memories, colonial legacies, ethnicity and foreign linkages.

These motivations transform into dangerous expressions leading to drastic

consequences for the individual states and societies as well the region as a

whole, as shown in Figure-4.[8]

The ultimate product of this complex nature of security environment is an

unremitting instability, which leads to primacy of militarism rather than

humanism. Key

manifestations of security paradigm are (Figure-5):[9]

inter-state wars; intra-state insurgencies; conflict management rather than

resolution; an unending conventional arms race; nuclearization (of India and

Pakistan); interventional politics i.e. regional intervention; extra-regional

intervention (e.g. presence of foreign forces in form of International Security

Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan);[10]

and human insecurity, which is a by-product of some of these and a cogent

reason for others.

This has embedded a sort of mini Cold War

in the region especially in case of the two largest countries i.e. India and

Pakistan, which keeps playing its role even in softer human affairs like sports and cultural activities.

For instance, a cricket match between India and Pakistan is taken nothing less than a military

encounter, though in non-kinetic form, by many people of two countries.[11]

It

is of note that South Asia

is home to the world’s oldest surviving UN mission, United Nations Military

Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP). The UNMOGIP dates back to January 1949 and

operates on either side of the Ceasefire Line (now the Line of Control)

between the two parts of Kashmir; Azad Jammu and Kashmir, and Indian-Occupied

Kashmir.[12]

India-Centric

Regional Disputes

The region is home to the world’s largest

territorial disputes. Important to note is that most of them involve India,

thereby instituting an India-centric security paradigm in South Asia. Key ones

to name are: India-China

Aksai Chin dispute; India-China South Tibet/ Arunachal Pradesh dispute;[13]

India-Pakistan Kashmir dispute; India-Pakistan Sir Creek dispute;

India-Pakistan dispute over construction of dams by India in violation of the

Indus Water Treaty; Pak-Afghan argument over cross border movement of

militants; India-Bangladesh border dispute over 51 Bangladeshi enclaves and 111

Indian enclaves; India-Bangladesh sea boundary dispute over New Moore/ South

Talpatty/Purbasha Island in the Bay of Bengal;[14]

India-Bangladesh Farraka Dam dispute; India-Nepal Boundary dispute including

400 squares kilometres on the source of Kalapani River; and India’s argument

over militants’ crossing with Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma and Bhutan. Figure-6

illustrates.[15]

Kashmir, nevertheless, remains the site of

the world’s largest and most militarized territorial dispute.[16]

It is often referred to as a nuclear flash point on the globe. Kashmir is not only an

unfinished agenda of the partition but also an unresolved dispute of the

UN. The UNSC adopted various resolutions in 1948, 1949, 1950 and 1951 to

resolve the issue democratically but it has yet to succeed. For instance, in

1951 the UNSC, through a resolution endorsed, “Reminding the governments and

authorities concerned of the principle embodied in its resolutions 47 (1948) of

21 April 1948, 51 (1948) of 3 June 1948 and 80 (1950) of 14 March 1950 and the

United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan resolutions of 13 August 1948 and 5 January 1949, that the

final disposition of the State of Jammu and Kashmir will be made in accordance

with the will of the people expressed through democratic method of a free and

impartial plebiscite conducted under the auspices of the United Nations…”[17]

To

this end, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had articulated: “I should like to make it

clear that [the] question of aiding Kashmir in this emergency is not designed

in any way to influence the State to accede to India. Our view, which we have

repeatedly made public, is that [the] question of accession in any disputed

territory or State must be decided in accordance with the wishes of the people

and we adhere to this view.”[18] He

further pronounced, “We have declared that the fate of Kashmir is ultimately to

be decided by the people. That pledge we have given, and the Maharaja has

supported it, not only to the people of Kashmir but to the world. We will not,

and cannot back out of it. We are prepared when peace and law and order have

been established to have a referendum held under international auspices like

the United Nations. We want it to be a fair and just reference to the people,

and we shall accept their verdict. I can imagine no fairer and juster [sic]

offer.”[19]

The

plebiscite could never be held. The issue not only remains unresolved but is

even more complicated today. More than the territorial area or geo-strategic interests

of the nations, Kashmir is a human security issue for millions of people, some

of whom are living in a split family status and many of them as refugee for the

last about seven decades. The territorial area of Kashmir is 222,236 square

kilometres (total on both sides of the Line of Control). It is only a little

less than the United Kingdom’s 243,610 square kilometres and more than the

territorial areas of Bangladesh (143,998 square kilometres) and North Korea

(120,538 square kilometres), and virtually double the area of Bulgaria (110,879

square kilometres). It is nearly five times larger than the territorial areas

of Denmark (43,094 square kilometres) and Netherlands (41,543 square

kilometres). These figures have been given to put it in comparative perspective.

The South Asian nations also have hosts of non-territorial arguments.

Interstate Conventional Wars

The

territorial and

non-territorial issues have, in the past led to wars between India and Pakistan

in 1948, 1965 and 1971, and India and China in 1962. Skirmishes between India and Bangladesh border

security forces are also a routine bulletin in the region. Besides, the Line of Control

(formerly the Ceasefire Line) in Kashmir is in a virtual state of war since

1947.

Intrastate Arguments and Insurgencies

All

the eight South Asian nations are home to different types of ethnic arguments,

confrontation, insurgencies, violence and militancy. The key ones to note are: Taliban Movement in Afghanistan

and Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan;[20]

Maoist insurgency in seven

out of total 28 states of India (aptly termed as the seven sisters); Naxilite insurgency in India,

which Dr Manmohan Singh, the Indian Prime Minister, termed as the single

biggest internal security threat[21]

(the area affected by Naxilism is popularly termed as the Red Corridor);[22]

LTTE in Sri Lanka;[23]

the Maoists insurgency in

Nepal, which lasted till 2006 and is passing through post-culmination

settlement phase; and insurgency in Chittagong Hill Tracts region of

Bangladesh.[24]

As

a matter of fact, there are hundreds of militant organizations operating in

South Asia.[25]

Take the case of India;

there are virtually 200 armed terrorist organizations / groups – most of them

from the majority Hindu community – that have picked up arms against the

state and minority communities with one motive or the other.[26]

Recently, India’s Union Home Minister Sushil Kumar Shinde stated, “We have got

an investigation report that be it the RSS or BJP, their training camps are

promoting Hindu terrorism. We are keeping a strict vigil on all this. We will

have to think about it seriously and will have to remain alert.”[27] This is too late a confession, indeed. A lot

of damage has already been done.

South

Asia has now become home to transnational terrorism with streaks of global

terrorism, too. Pakistan

and Afghanistan are facing the worst kind of terrorism on the globe with

international and regional terrorist organizations operating in the

mountainous border region receiving support from other countries.

Regional Interventions

Interventional politics is part

of the security paradigm in South Asia. While it is true in some other

cases too, India,

the largest country both in terms of territory and population and with hegemonic desires and designs,

has never missed an

exploitable opportunity in any country of the region. Indian intervention in Sri Lanka

in form of Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in 1987 was a militaristic

expression, still fresh to the memories of the Sri Lankan people.[28]

India has always been interfering

in Balochistan province of Pakistan during various rounds of militancy there.

It is also using its presence in Afghanistan to nurture trouble in Pakistan. To

this end, Charles Timothy

Chuck Hagel, the 24th US Secretary of Defense, in a speech at

Oklahoma’s Cameron University in 2011, articulated without mincing a word:

“India for some time has always used Afghanistan as a second front … India has

over the years financed problems for Pakistan on that side of the border.”[29]

Earlier, Dr Christine

Fair, a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, said in 2009: “I

think it is unfair to dismiss the notion that Pakistan's apprehensions about

Afghanistan stem in part from its security competition with India. Having

visited the Indian mission in Zahedan, Iran, I can assure you they are not

issuing visas as the main activity. Moreover, India has run operations from its

mission in Mazar and is likely doing so from the other consulates it has

reopened in Jalalabad and Kandahar along the (Pak-Afghan) border.”[30]

India has expanded and extended

its military presence in the region. It is particularly expanding westward. For

instance, it has declared diplomatic presence in eight cities of Iran and Afghanistan to include:

Iran – Embassy in Tehran and consulates in Bandar Abbas and Zahedan;

Afghanistan – Embassy in Kabul and consulates in Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat,

Jalalabad and Kandahar. Besides, it has declared non-diplomatic presence

both in Iran and Afghanistan. Its largest project in Iran is revamping of Chahbahar port.

India is running 84

different projects in Afghanistan especially in the provinces of Kandahar,

Zaranj, Herat, Mazare-e-Sharif, Pul-e-Khumri and Kunar.[31] There

is strong evidence that the Indian intelligence agencies are working as part of

all these projects. India has extended its outreach beyond Afghanistan. An Indian Air Force (IAF) fighter

squadron of MiG 29 is stationed at Farkhor Airbase, some 130 kilometres

southeast of Tajikistan’s capital Dushanbe since 2004-05. Earlier, India

had renovated Ayni airbase located 15 kilometres west of Dushanbe at a cost of

$70 million.[32]

Later, they changed the plan and stationed the IAF squadron at Farkhor.

Certainly, India has stationed these to pursue strategic military objectives

and not to carry out humanitarian activities. India has also established a

naval listening post in northern Madagascar, off Africa’s east coast, to gather

intelligence on foreign navies.[33] Indian

naval presence is also reported around Jaffna and Trincomalee Harbour in Sri

Lanka, the Maldives and Strait of Malacca. This is, indeed, a brief picture of

India’s military activities beyond its borders aimed at strangulating the

countries of the region.

Conventional Forces

South

Asian nations are maintaining

large-size conventional military forces to clothe the idea of traditional state

security. The active duty manpower in the armed forces of six countries

is 2,548,000 soldiers. Country-wise manpower is shown in Figure-7.[34]

This does not include the manpower of civil armed forces (CAF), other second

line forces and task-specific security forces. The figures of remaining two

countries i.e. Bhutan and Maldives have not been included being insignificant.

Even the active armed forces manpower of the six countries mentioned herein is

more than the individual population of 195 countries and semi-independent

entities of the world. It is more than the total population of Australia, New

Zealand, Yemen and Ghana (individually). Also, it is more that the population

of three South Asian countries to include Sri Lanka, Bhutan and Maldives

(individually), a little more than the combined population of Sri Lanka and

Maldives, and more than double the combined population of Bhutan and Maldives.[35]

On the average, South Asia has nearly one active duty soldier to each square

kilometre of territory, whether inhabited or uninhabited.

The security environment has led to a

unique kind of arms race in the region. Domestic arms production and

acquisition of military equipment from abroad continues. Indigenously, India

and Pakistan are producing, assembling or overhauling fighter jets, helicopters,

tanks, armoured vehicles, warships, submarines, frigates, artillery guns, small

arms, mines, grenades and a lot more. On

the whole, South Asia’s military expenditures have seen an increase of 41% from

1999 to 2008.[36] India became the 10th

largest defence spender in the world in 2009[37] and

the 8th largest in 2012. South Asia’s military spending are given in

Table 1.1.[38]

Table 1.1: Military Spending in South Asia 2012

(previous years in some cases)

|

Country

|

Military

Spending

(US$ billions)

|

World Ranking

|

|

India

|

46.219

|

7

|

|

Pakistan

|

5.16

|

33

|

|

Sri Lanka

|

1.280

|

65

|

|

Bangladesh

|

1.137

|

68

|

|

Afghanistan

|

0.250

|

97

|

|

Nepal

|

0.207

|

104

|

Source: SIPRI

Yearbook 2013.[39]

It may be seen that India is spending at least 7 to 8 times more

than the total defence budget of remaining South Asian countries. It is also of note that these

are the expenditures declared through annual budgets. Actual outlay is

certainly more than that as several military activities remain discreet and

unannounced. Such activities include impromptu defence purchases from abroad,

expenditures on intelligence agencies/ activities, and the expenditures on

unconventional forces e.g. nuclear and missile programmes. This consequently

eats into the public taxes and national capital which could otherwise be spent

on the well-being of the hapless populace.

Nuclearization

This

is yet another thread of South Asia’s security paradigm. The Small Nuclear

Forces predicted in South Asia in mid-1980s are not as small now.[40]

As of today, located in the Eastern Nuclear Cauldron (Figure-8),[41] India

and Pakistan have sizeable arsenals of ballistic missiles and nuclear warheads

– enough to wage a wide-ranging war even though nukes are being used as weapons

of foreign rather than defence policy, and war prevention rather than war

fighting. Albeit one nuclear bomb is sufficient to destroy a city of the size

of Hiroshima or Nagasaki, or even Delhi or Lahore in case the circumstances

lead to nuclear war fighting, however, reports indicate India and Pakistan to

be possessing dozens of warheads. One of the sources puts it at 60 to 80

nuclear warheads in case of India and 70 to 90 possessed by Pakistan.[42]

India-China Rivalry

South

Asia’s security environment has numerous extra-regional linkages too. India-China border dispute has

the biggest shadow on the security environment of South Asia. India-China rivalry, indeed,

goes beyond the disputes over Aksai Chin and South Tibet (Arunachal Pradesh). Both are vying

for regional dominance and a pronounced role in global affairs. Consequently,

both are pursuing to extend their strategic security parameter. India-China

maritime rivalry in the Indian Ocean in order to control the strategic sea

routes is a real time issue. They do not share maritime border; yet, they are

emerging as rivals to dominate the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean. The

littoral areas are coming up as the new combat zone. For instance, China has

built naval facilities, radars and signal-intelligence (SIGINT) posts all along

the Myanmar coast and in Coco Islands. On the other hand, India and Myanmar

signed Kaladan River transportation agreement in April 2008 that involves

India’s upgradation of Myanmar’s Sittwe Port. Likewise both have a competition to control the Strait of

Malacca, a choke point between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, which is

extremely important for China for its strategic supply lines. In 2005, India

started conducting naval patrolling with Thailand in the Andaman Sea.

Although the patrols were primarily directed against maritime crimes, these

also served to restrict Chinese activities in the area.[43]

Extra-Regional Linkages and

Interests of Major Powers

Extra-regional

linkages and interest of major powers in the region is yet another and very

important dimension of South Asia’s security paradigm. India-US and

India-Russia nuclear deals have further exacerbated the security environment of

the region and paved the way for arms race at the expense of socio-economic

development of over 1.57 billion people of the region. Presence of foreign forces in Afghanistan, in

Central Asia, over Arabian Peninsula and in the Indian Ocean is but one such

manifestation of the issue. Extra-regional intervention like ISAF/NATO in

Afghanistan has overshadowed the entire gamut of regional security.

Drone attacks in Afghanistan and FATA of Pakistan have added a new dimension to

the security landscape of the region. The drone issue has generated an extended

debate across the globe, which is likely to lead to some logical end.

Human Insecurity

Human

security in South Asia is overshadowed by the primacy of traditional state

security.[44]

National exchequers, which could otherwise be spent on well-being of over 1.57

billion South Asian people, are rather a source of sustenance for state

security mechanism. Human

security is not a priority in regional security arena due to longstanding disputes

and shared threat perceptions, which instead work towards reinforcing

the state security system. The region is home to largest number of

adult illiterates, largest number of out-of-school children, largest number of

unemployed adults, largest number of households without electricity and tap

water, largest number of malnourished individuals and largest number of people

suffering from lack of access to basic health facilities in the world. The list goes on and needs an

independent study to deal with the subject. In sum, human security is held

hostage to the traditional security and cannot be improved till such time that

the security paradigm is balanced between traditional and non-traditional

security needs.

Conflict Resolution: the

Limiting Factors

Conflict prevention, conflict

management, conflict settlement and conflict resolution are different facets of

statecraft. In case of South Asia, these are neither being desirably debated in

academic circles, nor being implemented at policy level in a desired fashion.

More often than not, the political leadership of South Asia is found boasting

about their efforts on the way of peace. However, “peace” to them often means

conflict prevention or management, and certainly not conflict settlement or

resolution.

Conflict

resolution takes place through political process. Media, intelligentsia, think

tanks and civil society facilitate the process by providing platforms for

discussions and negotiations, and cultivating the environment for political

initiatives. In case of South Asia, the entire process is corroded and complete

procedure is flawed. The most critical element in conflict resolution is for

the parties to seek resolution. If policy-makers do not believe that they can

achieve by unilateral action what they want, they look for alternatives. This

is the stage where there is some scope for conflict resolution.[45] Harold

Hal Saunders, the United States Assistant Secretary of State for Near East

Affairs between 1978 and 1981, noted: “In many cases, developing the commitment

to negotiate is the most complex part of the peace process because it involves

a series of interrelated judgments. Before leaders will negotiate, they have to

judge: (1) whether or not a negotiated solution would be better than continuing

the present situation; (2) whether a fair settlement could be fashioned that

would be politically manageable; (3) whether leaders on the other side could

accept the settlement and survive politically; and, (4) whether the balance of

forces would permit an agreement on such a settlement. In more colloquial

language, leaders ask themselves: How much longer can this present situation go

on? Is there another way and could I live with it politically?”[46]

Certainly,

the states are the key parties to the conflicts such as those faced by South

Asia. States are represented by their institutions like the governments and

political parties, etc. South Asian leadership does not show political will to

settle or resolve the contending issues. Dispute, both territorial and non-territorial

are used as political slogans and election cards. In case a given political

party shows some leaning to move a mile forward on the way of peacemaking and

conflict resolution, the contending political parties pull the process back by

a myriad mile by demonizing the political party showing resolve as “being

involved” in national “sell-out.” India has a worst history in this regard.

Indian think tanks often reverse the political process. They are mostly found

involved in research and reflection on conflict rather than peace, terrorism

rather than counterterrorism, and state security rather than human security.

One cannot name a single research institute or think tank in India, which would

go against popular content or conventional wisdom apropos conflict resolution

in South Asia albeit India itself is the centre of conflict in the region due

to various types of disputes with all countries bordering it.

Recommended Regional Security

Framework

International

experience shows that the regional security paradigm can best grow and sustain

under a cooperative, comprehensive and holistic framework facilitated by

meaningful conflict-resolution endeavours. The formats of European Union (EU),

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the Association of

Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), Shanghai

Cooperation Organization (SCO) and African Union (AU) etc bear testimony to the

fact. South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), on the other

hand, has rather reduced to a meet, greet and depart forum. South Asia

must also embrace the notion of a comprehensive, cooperative, collaborative,

integrative and all-inclusive security paradigm. Recommended framework is as

follows:

Resuscitation and Revitalization of SAARC: For

the purpose of regional approach to conflict-resolution, SAARC should be both

resuscitated and revitalized. The SAARC Charter needs to be expanded and redefined with the regional

security as an imperative and the foremost article.

South Asia Security Dialogue (SASD): In

line with OSCE and ARF, South Asia should institute SASD from the platform of SAARC. SASD should involve all SAARC states

as members and US, EU and China as facilitators. SASD should primarily

work to resolve the impending territorial and non-territorial disputes in the region. This institution should consist

of various working groups (WGs) for each dispute in the region. All

issues should be discussed, debated and dialogued at working groups level

involving officials, civil society representatives and global enablers. WGs should formulate their

recommendations for the policy level. In case of crosscurrents between

two or more issues, joint working groups may be formed. The progress is

dependent on the political will of the leadership. Hence, if one issue is not

resolved, it should not cast back on resolution of the other issues. If SASD

functions in line with the spirit of this proposal, it would help resolve the

regional disputes in a graduated manner.

South Asia Nuclear Dialogue (SAND): SAND

should be established as a corollary to the SAARC in line with SASD with same

membership and facilitation level. SAND should first help India and Pakistan to work on nuclear risk

reduction and nuclear-cum-missile restraint measures. Then, it should work

to persuade the two

nations on maintenance of minimum credible deterrence rather than maximum

possible deterrence. If SASD succeeds in resolving major disputes in

South Asia, especially between India and Pakistan, SAND should work on de-nuclearization

of the region.

Conventional Arms Reduction Dialogue

(CARD): Conventional

arsenals of all South

Asian countries are swelling with each tick-of-the-click. Likewise,

against the global winds of reduction in the size of standing armies, South

Asians are moving uphill. Major share of the defence budget is consumed either

on manpower related administrative aspects or production and purchase of

military hardware. Certainly, India shares greater burden due to the India-centric disputes and security

paradigm in the region. CARD, which should be composed and organized in

line with SASD and SAND, should work with the states of the region on reduction

of conventional arms as well as manpower. The states would, thus, be able to

divert the capital spared by reduction in defence budgets to address the human

security issues.

South Asian Parliament (SAP): The

case of a South Asian

Parliament (SAP) may be considered as an organ of SAARC. It may comprise

equal number of members

from all eight countries of the region. Ten members from each state is a respectable figure.

The membership may be based on ex parliamentarians, intellectuals, media

persons, lawyers and experts in different fields. Speakership of SAP should revolve between the member

states on biannual basis. This means that the turn of each country would come after four

years. The purpose and mandate of SAP should be to provide an interactive forum, serve as a

regional forum for exchange of ideas and proffer recommendations to the member states

on important issues of mutual interest.

Confidence Building Measures (CBMs):

CBMs at the level of state are of utmost importance for the

purpose of creating a dialogue-supportive environment based on mutual-trust.

CBMs are to be initiated

alongside the proceedings of SAARC, SASD, SAND and CARD. A number of

measures may be initiated by the states. Key ones are: relaxation of visa requirements for movement of

people within the region; visa-free movement of the people of Kashmir on either

side; setting free each other’s prisoners as a good will; issuance of friendly

rather than inflammatory statements by national leaders; tangible cessation of

interference in each other’s affairs and reduction of forces on borders. In

case of India-Pakistan relations, India has always talked of CBMs, which

would consequently cultivate environment for dialogue on major issues including

the core issue of Kashmir. It is considered that talks on the territorial

disputes are the biggest leap on the way to confidence building and mere

“people-to-people” gestures as often advocated by India can be of no use.

People-to-People Contacts (PPC):

PPC at the level of societies would help cleanse the

stains of historical memories and reduce tension. Inter-parliamentary commissions

and dialogues, and forums of interaction between the people from various walks

of life e.g. investors, traders, students, media persons, academics and

intellectuals will be of the essence in this regard. People will

certainly seek to concentrate on human security rather than the traditional

state security. Eventually, this would work as a complimentary axis of conflict

resolution.

Multi-Tracked Diplomacy (MTD):

MTD has helped in easing up tension in

South Asia in the past. A host of models may be adopted and put into action on

the sidelines of other initiatives. It could take the shape as follows: Track-1, state-to-state meets

between the diplomats and officials; Track-2, regional diplomatic ventures

involving more than one (or all regional) states; Track-3, societal engagement

involving the civil society and citizenry; and Track-4, involvement of global

enablers in Track-1 or 2 or combination of both.

Intra-Region Trade: Intra-region trade in

South Asia is abysmally low. South

Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), which could have been the greatest success of

SAARC, is held up due to security moorings of the SAARC members. The

states have, heretofore, preferred to work on either bilateral/ preferential trade agreements within

the region or are depending on extra-regional trade. SAFTA should not only be

signed and ratified by all SAARC members but should also be put into action in

keeping with the universal definition of free trade. It should be taken as a

comprehensive subject. Trade should not only mean the duty-free flow of

goods across the borders but should also involve provision of investment

opportunities and free movement of labour.

Human Security under all Circumstances: It is imperative for the South Asian leadership to agree to

at least one fundamental

agenda that the people would remain a priority under all circumstances

and that the human security aspects would not be interfered with even during

warlike situations. SAARC should help bring the states and societies closer.

The human security spheres in which it can be of use are as follows:

inter-state transfer of experience; trade; education and literacy; healthcare

including combating epidemics; environmental security and disaster management;

food security; river water-sharing treaties and agreements between the states;

and resolution of ethnic discords.

South Asia Literacy Commission (SALC): Illiteracy is the worst human security

challenge faced by South Asia. To

combat illiteracy at regional level so as to complement the efforts of the

states, it is recommended to institute SALC under the auspices of SAARC. It should be formed as an

independent body and should have its membership based on reputed educationists.

The governments should

only be interacting with SALC for the purpose of funding and facilitation, and

should have no role in its proceedings. SALC should be monetarily supported by South Asia

Literacy Fund (SALF), a subsidiary established for the purpose, the management

of which should fall in the realm of SALC. The Commission should launch

a targeted campaign against illiteracy opening area-specific SALC institutions

including at least one world class university in each country with teaching staff

from all member states but students from the host country. SALC technical

institutes should be established in all member states in keeping with the

requirements of host state. It should also establish elementary education

institutes in the areas with high illiteracy rate. Later, the spheres of its

activities may be expanded by establishing more universities and institutes.

SALC should also be utilized as a forum for inter-state movement of students

for studying in public and private institutions of any SAARC member country.

South

Asia Free Media Association (SAFMA): SAFMA already exists as an institution of SAARC. Nevertheless, there is a dire need

to revitalize it. SAFMA can help create and maintain a dialogue-supportive

environment. The institution itself needs to work out a code of conduct

for being a collaborator rather than contender, and an institution for regional

integration rather than a mouthpiece of any single state.

Conclusion

South Asia is in need of introspection

more than ever before. It has remained in a perpetual state of war in

traditional and nontraditional forms for the last many decades. Must it reach

the mark of a 100-year war? Such a proposition would, certainly, be useless

both for South Asian states and societies, and individuals and communities.

Hence, there is a need to tilt the mass of regional security paradigm from

traditional state security to human security. It is of note that whereas

traditional state security is often based on perceptions, human security is a

manifestation of shared realities. It must be noted that no state of the region

would relegate the traditional state security paradigm due to the nature of

conflict. However, the acme of leadership would be to create and maintain

balance between state security and human security in a manner that both

complement each other.

South Asia has a great potential to

progress in the comity of nations on the globe, if it embraces the concept of

human security as part of a cooperative and comprehensive security paradigm.

Human security of virtually 1.57 billion people would certainly work to

complement the state security. For this, the South Asian leadership needs to

depart from a tested but failed system of state security and embrace an all-acceptable

notion of human security. An adequate level of human security achieved as a

consequence would surely ensure the security of states too, thereby re-modeling

the security paradigm in a universally accepted fashion.

International community is expected to

share some burden by making possible a dialogue for the purpose of

conflict-resolution in South Asia. This would have dividends not only for the

South Asians but for the entire world. Success of the world community would

surely boost up the confidence of the one-fourth of the human race living in

South Asia in the global leadership. This would also help make a concrete case

for denuclearization and arms reduction in the region. In sum, dividends are

countless but need regional as well as global resolve; the earlier, the better!

[1] Rob Johnson, A region in

turmoil: South Asian conflicts since 1947 (London: Reaktion Books Ltd,

2005), 7.

[2] Map by the writer. UN Map of

South Asia also shows Afghanistan as part of the region. Details may be found

at “UN map of South Asia,” www.un.org/depts/Cartographic/map/profile/Souteast-Asia.pdf (accessed June 29, 2013).

[3] Illustration by the writer.

Data obtained from CIA – the World Factbook,

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2119rank.html

and

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2147rank.html?countryName=United%20States%20Pacific%20Island%20Wildlife%20Refuges&countryCode=um®ionCode=au&rank=237#um

(accessed December 9, 2009).

[6] “Highest Mountain Peaks of the

World,” National Geographic Society, quoted in

http://www.abell.org/nal/PDFs/World_Stats/Highest%20Peaks%20in%20the%20World.pdf

(accessed December 11, 2009).

[7] Article 53-54 to Chapter VIII

of UN Charter.

[8] Conceptualized and illustrated

by the writer.

[10] A part of ISAF may withdraw from

Afghanistan in 2014, as announced by the US and NATO. However, presence of

foreign forces in and around the region is likely to remain a reality during

the decades ahead.

[11] The word military encounter

used metaphorically considering the response of emotionally charged (more than

passionate) crowed. In some cases it has led to very untoward incidents in

matches between India and Pakistan.

[12] Further details may be found at

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unmogip/facts.html (accessed July 8,

2013).

[13] The disputed territory is

located south of the famous McMahon Line agreed to between the Britain and

Tibet as part of the Simla Accord signed in 1914, which China has never

endorsed as the Tibetan government was not sovereign and thus did not have the

power to conclude treaties with other countries. Indo-China War of 1962 took

place over the same dispute.

[14] Interestingly, some common

Indians claim the Indian Ocean to be belonging to India. Likewise, common

Bangladeshis too lay a complete claim on the Bay of Bengal.

[15] Illustration by the writer.

[16] CIA – The World Factbook,

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/in.html (accessed November 29, 2009)

[17] UNSC Resolution 90 (1951) dated

31 January 1951.

[18] J. C.

Aggarwal and S. P. Agrawal, Modern History of Jammu and Kashmir:

Volume I - Ancient Times to Shimla Agreement (New Delhi:

Concept Publishing Company, 1995), 35.

[19] Jawaharlal Nehru, Independence

and After: A Collection of Speeches, 1946-1949 (New York: The John Day

Company, Inc., 1950), 59. Originally published by the Publication Division,

Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Delhi. Reprinted

by the John Day Company in 1950 and 1971.

[20] Taliban are one of the fiercest

armed group in South Asia and the biggest security challenge facing the

prospects of peace in the region.

[21] “Rahi Gaikwad: Manmohan:

Naxalism the greatest internal threat” The Hindu, New Delhi, October 12,

2009.

[22] Armed Marxist revolutionaries

known as Naxilites – named after the 1967 revolt by farmers in the West Bengal

village of Naxalbari, which spreads across the poor Indian states. “Kapil

Komireddi: Blood runs India’s Red Corridor” The Guardian, April 23,

2009.

[23] Albeit, the LTTE has been

overpowered by Sri Lankan Armed Forces in 2009 and the LTTE Chief Vellupillai

Prabhakaran was killed, yet, the threat exists in form of the LTTE ideology and

many Sri Lankans fear that they might rise head again.

[24] The conflict in the Chittagong

Hill Tracts (CHT) dates back to pre-Bangladesh times, when it was East

Pakistan. CHT saw a fierce insurgency

from 1977 to 1997 waged against the government by (United People's Party of the

Chittagong Hill Tracts and its militant wing named the Shanti Bahini). They

demanded autonomy for the indigenous people, the Chakma people, who are mainly

Buddhists, Hindus, Christians and Animists. The insurgency has officially

receded since 1997 but the conflict continues as the roots of conflict exist.

[25] There are so many militant

groups in South Asia with so long a list of dreadful acts that it needs a

separate and all-inclusive study to cover and conclude.

[26] Ehsan Mehmood Khan, Human

Security in Pakistan (Islamabad: Narratives, 2013), 22.

[27] For details see, “BJP, RSS conducting ‘terror training’

camps, says Shinde,” The Indian Express, January 21, 2013.

[28] Details may be

found in a number of topical accounts e.g. Depinder Singh, The IPKF in Sri Lanka (New Delhi: Trishul Publications, 1992).

[29] Rama Lakshmi, “Chuck Hagel

confirmed in Washington, but doubts remain in India,” The Washington Post,

February 27, 2013.

[30] “What is problem with

Pakistan?” Foreign Affairs,

http://www.foreignaffairs.com/discussions/roundtables/whats-the-problem-with-pakistan

(accessed on July 1, 2013).

[31] Peter Wonacott, “India

Befriends Afghanistan, Irking Pakistan,” The Wall Street Journal, August

19, 2009.

[32] Matthew Stein, “Compendium of

Central Asian Military and Security Activity,” Foreign Military Studies

Office (FMSO), Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027 (October 3, 2012): 2-6.

[33] Siddharth Srivastava, “India

drops anchor in the Maldives,” World Security Network, September 2,

1009,

http://www.worldsecuritynetwork.com/India/siddharth-srivastava/India-drops-anchor-in-the-Maldives

(accessed July 1, 2013).

[34] Illustration by the writer.

Data obtained from Anthony H. Cordesman, Robert Hammond and Andrew Gagel, “The

Military Balance in Asia: 1990-2011, A Quantitative Analysis,” Center for

Strategic and International Studies, Washington D.C. (May 16, 2011): 93.

[35] List available at “Country

Comparison: Population,” CIA – the World Factbook,

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2119rank.html

(accessed July 5, 2013).

[36] “Military expenditures by

region,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI),

http://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2009/05/05A (accessed December 8, 2009).

[37] “The top ten military

spenders,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI),

http://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2009/05/05A (accessed December 8, 2009).

[38] SIPRI Yearbook 2013, “Armament,

Disarmament and International Security.” Stockholm International Peace

Research Institute (SIPRI), www.sipriyearbook.org (accessed July 5,

2013).

[39] SIPRI Yearbook 2013, “Armament, Disarmament and International

Security.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI),

www.sipriyearbook.org (accessed July 5, 2013).

[40] Dr. Thomas Blau and others,

“Small Nuclear Forces in South Asia,” in Small Nuclear Forces and U.S.

Security Policy, ed. Rodney W. Jones (Lexington Books: Lexington: 1984), 89

to 107).

[41] The term being introduced by

this writer herein for the first time considering that there are two nuclear

cauldrons in the world: Eastern Nuclear Cauldron comprising China, North Korea,

India, Pakistan, Israel, and (nuclear aspirant) Iran; and Western Nuclear

Cauldron comprising the US, Russia, the UK, and France. The nuclear weapon

states have been so categorized bearing in mind their location and areas of

nuclear interest. Russia’s case is a bit different. Considering its location,

it falls into the Eastern Nuclear Cauldron but from the point of view of its

nuclear interests, it is part of the Western Nuclear Cauldron. At any rate,

Russia’s nukes have been, and are still, playing a role in the security

paradigm of the West more than the East.

[42] “Status of

World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists,

http://www.fas.org/programs/ssp/nukes/nuclearweapons/nukestatus.html (accessed

December 12, 2009).

[43] Gurpeet S. Khurana,

“China-India Maritime Rivalry,” Indian Defence Review, April 2009.

[44] As against state security, in

which state is the only security referent, individuals and communities are the

key referents in case of human security. The concept of human security, though

still evolving, was given a normative paradigm in UNDP’s Human Development

Report (HDR) – 1994. According to HDR-1994, human security comprises seven

subsets to include: political security, economic security, personal security,

community security, food security, health security and environmental security.

Three more subsets to include women security, children security and education

security have been added in the Human Security Framework for Pakistan, which

may be applicable to other peer countries, proposed in Ehsan Mehmood Khan, Human

Security in Pakistan (Islamabad: Narratives, 2013).

[45] Sundeep Waslekar, A Handbook

for Conflict Resolution in South Asia (New Delhi: Konark Publishers, 1996),

4.

[46] Harold H. Saunders, The

Other Walls: the Politics of the Arab-Israeli Peace Process (American

Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1985), 24.